- Home

- Cyndy Etler

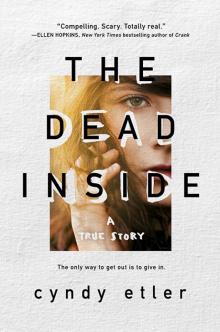

The Dead Inside

The Dead Inside Read online

Thank you for purchasing this eBook.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading!

SIGN UP NOW!

Copyright © 2017 by Cyndy Etler

Cover and internal design © 2017 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Connie Gabbert

Cover image © Nina Masic/Trevillion Images

Internal image © ISMODE/Thinkstock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. —From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

This book is a memoir. It reflects the author’s present recollections of experiences over a period of time. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Originally published as Straightling: A Memoir in 2012 in the United States by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

CONTENTS

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Reader

Sign In and Sign Out

1. Report any Suspicious-Looking Character on Grounds

2. Guys Must Wear Shirts—Girls Must Wear Bras

3. Knock on all Doors before Entering

4. No Talking in the Bathrooms

5. No Overalls or White T-Shirts in Group

6. No Borrowing Money, Candy, or Cigarettes

7. Permissions Must be Requested 72 Hours in Advance & be Okayed First by Parents, then Staff

8. No Hitchhiking or Picking Up Hitchhikers

9. No Making or Receiving Phone Calls or Letters

10. No Telling your Parents your Host-Parents’ Name or Phone Number

11. No Wearing Jewelry or Makeup

12. No Getting Out of Seat without Permission

13. Hang on Tight to Newcomers by the Belt Loop

14. No Hanging Out in Parking Lot

15. Host Home Doors and Windows Must be Locked and Alarmed

16. No Leaning or Slouching

17. No Lying Down while Writing M.I.S.

18. Everyone Must Wear Shoes and Socks

19. Open Meeting Introduction: Name, Age, Drugs, How Long on Drugs, How Long Here

20. No Animals in the Building

21. No Radio, TV, or Reading on First or Second Phase, except for Bible on Second Phase

22. No Leaving Group without Staff Permission

23. No Breaking Anyone’s Anonymity or Talking Behind Anyone’s Back

24. F.O.S. Lists go through a Fifth-Phaser, Up the Chain of Command, to Executive Staff

25. No Asking Parents for Wants and Needs During Talk

26. No Talking Out to Parents in Open Meeting Except for Saying “I Love You”

27. No Saturday Night Live or 98 Rock FM

28. No Newcomers Wear Belts

Epilogue: No Cameras, Tape Recorders, or Radios in the Building

A Note from the Author

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Back Cover

For all you “troubled teens,” who would totally stop being “trouble” if someone would just be nice to you.

NOTE TO READER

You’re not going to believe this. Seriously, nobody does. But this stuff happened, right here in America. In the warehouse down the street.

The warehouse had a name: Straight, Incorporated. Straight called itself a drug rehab for kids, but most of us had barely even smoked weed. Take me, for example. In September, at age thirteen, I smoked it for the first time. I tried it smoking again in October. In November, I got locked up in Straight—for sixteen months. The second we entered the building, we all stopped being kids. We stopped being humans. Instead, we were Straightlings.

Other than my father and me, each person you read about here has a fake name. Many of the Straightlings are smooshed-together versions of different people, but everything happened exactly how I describe it. If you want proof, hit the epilogue. There you’ll find court records, canceled checks, newspaper reportage, and Straight, Inc. internal documents. Want more proof? Go online and read all of the survivor stories that are just like mine.

And to my fellow Straightlings? Put your armor on. You’re going back on front row.

SIGN IN AND SIGN OUT

I never was a badass. Or a slut, a junkie, or a stoner like they told me I was. I was just a kid looking for something good, something that felt like love. I was a wannabe in a Levi’s jean jacket. Anybody could see that. Except my mother. And the staff at Straight.

So maybe I didn’t find a substitute family. Maybe I didn’t find love. I found other stuff instead. Pink Floyd, for example. And God, and Marlboro Reds. And Bridgeport, this city where it’s always dark, even at noon on Sundays. Only problem was, those were the exact things Straight used to prove you were an addict. You know: listening to druggie music, trying “gateway” drugs, running away from home…and then, before I could even learn how to smoke pot right, my mother trapped me in this warehouse full of teen savages. Straight, Inc.

From the outside, Straight was a drug rehab. But on the inside, it was…well, it was something else.

1

REPORT ANY SUSPICIOUS-LOOKING CHARACTER ON GROUNDS

The problem with me is that I never have the right pants. Think about it. When you go to the city, all you see are girls swiveling their hips, trying to make you notice the name on their butt. And it’s not just in the city. When I lived in Stamford, the recess yard at my elementary school was this cornucopia of designer jeans. All the girls had at least one pair from the good brands, and some girls had all four Jordache pocket styles.

Designer-jean girls are always named, like, Heather or Samantha or Jessica. They wear their richness all casual, like a perfume. I spent every recess on the sidelines—watching them, trying to learn popularity—while wearing my big sister Kim’s hand-me-down corduroys. I had three pairs, in a rainbow of depressing colors: beige, evergreen, and maroon. This one time, the three most popular girls in the whole sixth grade crossed the blacktop to get to me. I was all, Oh my God! Is this really happening? You can gues

s how that went.

Popular Girl: What brand are those jeans, Cyndy?

Me: These? These are a new kind of designer jeans—Garan. I have two Jordache and three Sasson at home, but I can’t wear them to school. Only on weekends, when I visit my boyfriend in Norwalk.

I was like, Yeah! Now they’ll really like me—I have designer jeans and a boyfriend! Here’s what she said back.

Popular Girl: Well, you call them Garan, but I call them Garanimals.

Oh my God. Garanimals is Sears-brand kids clothes, and Garan is totally the preteen version. She saw through my lie, and made me pay for it in front of everyone. What’s that disease where everybody stays away from you ’cause, like, your limbs are falling off? Oh yeah, leprosy. I’m a poor-kid leper in a rich girl’s world.

Once we moved out to Podunk Monroe though, the pants thing got easier. People in Monroe worship Levi’s, not designer jeans. And Levi’s have only one pocket design. So it’s a lot easier to keep up. Plus, since moving to Monroe—this is the really good thing—I get to steal my sister Kim’s best clothes since she’s never here.

Losing her stuff is just the price Kim pays for being so lucky. Seriously. How does she get to stay with some church family in Stamford for her senior year while my mother and step-thing Jacque move us to this hick town? Friday nights, I’m looking for a hiding place where Jacque and his itchy hands won’t find me while Kim walks around the Stamford mall, having guys whistle at her. I swear. If I didn’t need Him as a friend so bad, this could make me wonder if God’s even out there.

But actually, the friend thing has gotten better since I moved to Monroe. And it’s pretty much because of my pants. Well, Kim’s pants. When Kim does everyone a favor and visits Monroe, she switches the clothes she’ll bring back to Stamford. That’s how I get her good stuff. Last time she left behind the most awesome Levi’s ever. 501s! Button fly! And they fit me! So now, because I have 501s, I’m cool. And because I’m cool, I got my best friend. Joanna.

Joanna’s from Bridgeport, which is the murder capital of the United States. But her parents bought a second house in Monroe because Oh, it’s safe! And so pretty! Really, though? They bought a house here because it’s, like, one hundred percent white. Their Bridgeport house is right on the edge of Father Panik Village, which is where bad Masuk High boys go to buy drugs from black guys. And it really is a shady place, I guess. Joanna found a loaded gun in her backyard bushes. She thinks if she hadn’t showed it to her father, she’d still be living there. But now, instead, she lives in Monroe. Too bad for her, but lucky for me.

Joanna’s told me all about Bridgeport. In detail. When I picture it, I get this feeling like there’s a mountain of shattered glass in front of me, and I can reach out and touch it. It’s glittery and scary, and anything can happen there. And we’re going tonight and staying for the whole weekend!

So of course I’m wearing my 501s, plus my denim jacket. I’ve gotta wear my Keds since I have no other shoes, but here’s what’s good: I get to finally wear those Barbie-pink undies I found hidden in Kim’s dresser. You don’t even pull them on; you have to tie them on, with little ribbons on the sides! I’ve been saving them for a special dress-up occasion, but if tonight’s not special, I don’t know what is.

Joanna’s dad, Mr. Azore, looks like Mario from Donkey Kong. He’s short and wide, and he has that kind of mustache that curls at the ends. I really like him, because he laughs a lot. And whenever Joanna says, “Dad, I’m going out tonight. Can I have some money?” he hands her a twenty. A twenty.

Other than their laugh, Joanna is more like her mother. They’re built like the ladders Mario has to climb: tall and rectangular, with nothing extra up top. Listen, I friggin’ love Joanna, but she’s got bad eyeliner and guy hair. Sorry, Jo.

The ride to the Azores’ Bridgeport house is better than anything. It’s like freedom, like me and Jo are the dudes in a motorcycle movie. My window’s rolled all the way down, and Mr. and Mrs. Azore are so cool, they don’t make me roll it up when we get on the highway. I flip between asking Jo what we’ll do tonight—“Hang out. Go see what the guys are doing.”—and staring out the window, trying not to ask for more stories about “the guys.”

The changes in scenery remind me of kids’ book pictures, how they tell the story better than the words do. Outside the window in Monroe, it’s all boring, clean streets and fresh grass. But the longer we’re on the highway, the tighter and darker everything gets. Halfway to Bridgeport, in Trumbull, there are still trees, but the slabs of rock on either side of the road are all graffitied out.

Then you hit Bridgeport and bang! It’s like someone pulled down a screen. Everything’s suddenly gray. By the time you’re off the exit and going by the gas station, there’s nothing natural at all, just hunks of cars stripped down to shells and rocky dirt lots. But somehow you can tell, in the middle of all the deadness, this place is where real life happens.

So, like, life is pretty much perfect here. Joanna takes me out behind their house and shows me where she found the gun, and then we order pizza like it’s no big. By eight o’clock we’re out walking, four fives in Jo’s pocket and a curfew of “Not too late, girls.” Dag.

Joanna takes me by the houses of her Bridgeport friends, Mary and Torpedo Tits. And um…is it possible she wants to keep me all to herself? Because she didn’t even tell them we were coming. We have to sneak up and then run right past their houses. I’m trying really hard to be cool, but I can’t stop my hyena laugh, even when Joanna cups her hand around my mouth and says, “Shut up, Etler! They’ll hear us!” She’s laughing too, though, so I guess I’m all right. Damn, it feels good to have a best friend.

Next she takes me where the road curves a hard left because if it kept going straight, you’d drive right into the ocean. Joanna told me that a few years ago, some white boys from Westport forgot to turn their car when the road turned, so Bridgeport put three giant boulders there, to protect all the drug buyers from themselves. Now I guess these rocks are the Place, because as soon as we reach them, this young kid comes out of nowhere. He looks just like the kid in my favorite elementary book, J.T. The one about the bad little Harlem boy who makes friends with a one-eyed alley cat.

“Wanna cop?” he asks, his head level with Joanna’s boobs.

“Yeah. Gimme a dime,” Joanna says back to him, cool as fucking Fonzie.

Haloed by the streetlight, the kid slides a hand into his Adidas pants pocket. Then he palms out a bag the size of the lid on a fancy ring box. It’s fat with shreddy dark stuff. Joanna licks her pointer finger to slide one five, then another, off her wad of bills. She’s got all the time in the world.

The kid pinches the fives in their upper corners and snaps them so they’re straight, holding them up in front of his eyes. Then he gives us a nod.

“Later,” he says.

And he’s gone. And we have a bag of pot. What the fuck? We have a bag of pot.

“Oh my God, Joanna! What do we do now?”

If I was Kim, I’d know what to do. She’s just…cool. And that’s why I steal her stuff. When I wear her clothes, it’s a tiny bit like I’m Kim.

The best thing I stole from her is this pin I wear on my denim. It’s got the Rolling Stones lips on it, and underneath, in blurry letters, it says “Stoned.” Not Stones, Stoned. What’s cooler than that?

But with an actual bag of pot in front of me, I can’t even try to be cool. It’s useless. I’m totally that yippy cartoon dog at the chill bulldog’s heels. Soon Jo’ll reach a paw around and smack me.

But she doesn’t.

“Let’s go by the Zarzozas,’” she says, like I’m not a major embarrassment.

The Zarzozas are a bunch of brothers who make up half of “the guys.” When you first hear their name, you think their story will be beautiful too. It’s not. It’s a flower gone rotten, all slimy and black. When Jo first told me about them, I stopped f

eeling so bad about my situation.

The oldest brother is thirty, but he never hangs out, so he doesn’t count. The youngest brother is sixteen. His name is Tony, and he looks like Zorro. The middle brother is twenty-eight. He lives in the basement, and his name? It’s fucked up. One day, after taking a wicked crap, Dad Zarzoza starts fighting with the middle brother. To win the fight, the dad grabs his son by the neck and pushes his head into the toilet—which the dad hadn’t flushed. That brother’s been called Shithead ever since.

There used to be a mother, but Jo doesn’t know what happened to her. Oh, and Tony has the hots for Joanna. But she thinks he’s gross. “I am not going out with a kid whose father doesn’t flush it,” is how she put it.

The D’agostinos are the other half of “the guys.” They live down from the Zarzozas, on the ocean side of the street. Steve D’agostino, the guy Jo has a crush on, is fifteen. His brother Rich is twenty-five and too good for everyone, but he’ll party with Steve and his friends when there’s nothing else to do. Joanna points out their house as we walk by. It’s tiny and gray, and I wonder how a father and two brothers can all fit inside it.

Jo says Mr. D’agostino owns a fishing company, which explains the lobster traps all over the lawn. “Their dad’s out on the lobster boat most of the time,” she says.

For some reason we both laugh at that. It becomes funnier and funnier until we’re bent over, wheezing, and our sides hurt.

Up ahead, we hear different laughter, guy laughter. Four shapes loom out of the darkness like extras from the “Thriller” video. Their faces are in shadow, featureless as olives. All I can tell is they’re white and male and wearing a lot of denim. “Woahhhh!” one of them says. Then there’s more laughter.

Joanna has this crooked grin on, so the ghouls must be her friends. She slaps her hand on my back, and together we walk forward. Good, Cyndy. Good dog.

“Dudes,” Jo says.

And suddenly we’re surrounded by man-boys. I can tell which one is Tony Zarzoza. His hair is pitch black, and his lips and nose look royal. He’d be good to have as your boyfriend, if his dad wasn’t a shit pervert.

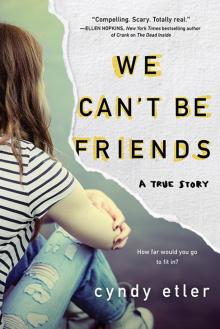

We Can't Be Friends

We Can't Be Friends The Dead Inside

The Dead Inside