- Home

- Cyndy Etler

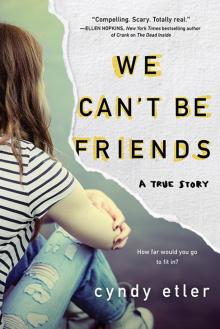

We Can't Be Friends Page 2

We Can't Be Friends Read online

Page 2

“Amen,” her mother says from the front seat. Her father hits the blinker and smooths into the fast lane.

We left the Straight building at 9:30 p.m. We’ll get to her house at 11:30. We’ll lie on a mattress from midnight to 6:00. We’ll leave for the building again at 6:30.

Group Room

FIVE DAYS IN

“Cyndy Etlerrr! Where are you? Stand your ass up!” STAFF guy yells at the hundreds of us. “Cyndy still hasn’t gotten honest about her drug list, group! Day five, and she’s still singing the ‘Poor me, I only tried pot’ song. Can you believe it?”

I don’t think I have a mother anymore. I’m not sure I ever had a mother.

“Cyndy’s got some balls!” STAFF guy yells. “Who’s got something to say to Cyndy? Who wants to give wittle baby Cyndy some spit therapy?”

*Rahhhrrrrr!*

Group Room

SIX DAYS IN

I shake my hands in the air to get called on. I stand up. They stare at me.

“I—I want—I want to get honest, about the drugs I’ve done? Um, I smoked pot once in September, and again in October, but I heard somebody say something about hash one time, so maybe there was hash in the pot? Or like, hash…oil? So I’ve done pot, and hash, and hash oil…and one time I tried to kill myself by taking a bottle of aspirin, so I’ve also done over-the-counter drugs…and I did drink beer once, so I’ve done alcohol…”

“Good job, Cyndy!” STAFF says. “Group, are we proud of Cyndy? Tell Cyndy you love her!”

“Love ya, Cyndy!” they all say. The hundreds.

Group Room

EIGHT DAYS IN

STAFF stands me up in group.

“Say it, Cyndy. Say the words: ‘I am a drug addict.’”

“But I—I only—”

“You! Are! An! Addict! If you don’t admit it and accept Straight’s help, you’re going to die. In a gutter. With a needle jammed in your arm. You’ll be sucking Satan’s cock in a ditch somewhere! Say the words!”

“I—I—”

“Group, who wants to—”

*Rahhhrrrrr!*

Open Meeting: Hundreds of Parents and Straightlings

TEN DAYS IN

The mother is across the warehouse from me. This time, she stands up alone.

“You have to hold the mic right up to your mouth, Mom,” STAFF says. “Try again.”

“Cyndy? I—”

“MOM!” I say, without even realizing.

“SHHHHHHHH!” the hundreds say back to me.

The mother is talking into the mic. “The staff told me you won’t admit to your addiction, Cyndy. So I have to use my tough love to help you. I am not going to sign you out of the program. Ever. You can either work this program and graduate, or you can sit in that blue plastic chair until you turn eighteen.”

Ten days ago, when she left me here, I was fourteen. Six weeks before that, when I ran away from her house and her husband, I was thirteen.

She’s still going. “But if you sign yourself out? When you turn eighteen? Do not call me. Do not come to my house. You either admit to your addiction and work this program or you are dead to me. I love you, Cyndy.”

Today, I am ageless. I am dust. I am nothing.

Group Room

ELEVEN DAYS IN

“I’d like to get honest with the group? I’m Cyndy, and I do believe I’m a drug addict. The drugs I’ve done are pot, alcohol, hash, hash oil, and T-Thai weed? And over-the-counter drugs.”

“LOOOOOVE YA, CYNDY!”

2

JANUARY 1986–MARCH 1987

Group Room

TWO MONTHS IN

There’s a new girl three inches in front of me.

“You need to quit feeling sorry for yourself and get honest!” I yell at her face. “I don’t care that you’re only fifteen. I’m only fourteen! And I had the exact same pity party for myself when I got here.”

The fluorescent bulbs make my spittle, on her cheekbones, sparkle and glint.

“‘Wittle Baby Cyndy’ was my name, because I refused to face my addiction, just like you! What drugs have you really done? Spill it!”

Yesterday, she was fifteen. Today, she’s ageless. She’s dust. She’s nothing.

Group Room

SEVEN MONTHS IN

We’re all in a great mood because Mitch, everybody’s favorite, is tonight’s staff.

“Group, listen up!” Mitch yells. “Our friend Chris here turned eighteen today, and guess what? He put in for a withdrawal! Chris is ready to go out there and live drug free on his own! He doesn’t need you anymore, group. Who wants to say goodbye before he signs himself out?”

*Rahhhrrrrr!*

“Andrey!” Mitch says, pointing at a kid on the guy’s side. “You’re Chris’s host brother, right? Chris has been sleeping at your house, eating your parents’ food, for how many months? Give Chris a hug! Tell him you’ll miss—”

“YOU are going to DIE,” Andrey howls, jumping up and racing at Chris like a bullet. “To DIE, motherfucker. You need this fucking group to stay sober and alive! You go out there, you’re going to pick up the first beer you see! And that one beer? An addict like you? You’ll be dead in a week! Freedom is a slippery slope, bro. Have a good fucking funeral.”

“Love ya, Andrey!” we all scream as he sits back down. “Bye, Chris!”

Group Room

EIGHT MONTHS IN

“Group! Put your hands down! Eyes up here!”

We do it, lightning quick. We’ve never heard Mitch sound pissed before.

“You all are fucked. I am so scared for this group because you don’t give a shit about your sobriety and you don’t give a shit about each other.”

Mitch’s face is as red as his hair.

“Who remembers Chris? Chris, who signed himself out the second he turned eighteen because you fuckups didn’t hold him accountable? Who you let get away with self-pity and ‘I’ve got this’ fantasies? Chris is fucking dead. He fucking hung himself. Who wants to die at eighteen like Chris? Go ahead! I’ll throw the doors open! Seriously! Which of you fucking druggies wants to leave now?”

We sit here, still as stones. None of us are breathing. Mitch is breathing fire.

“You fuckups don’t know because we keep you safe and secure in this building twelve hours a day, but us staff, we hear it all the time: Straightlings fucking killing themselves. Did you know that? They go back out there, and they realize how fucked they are, and sayonara. Adios. G’bye. I could give you three more names of kids you know just from the past six months! It is deadly out there. You ungrateful pussies need to work your asses off to get fucking sober and to get each other sober. No, put your hands down. I don’t want to hear your feelings. Let’s have a fucking song. ‘Fire and Rain.’”

We try to sing because Mitch said to. We can hear the click of tears in each other’s voices.

March 1987

Open Meeting: Hundreds of Parents and Straightlings

SIXTEEN MONTHS, ONE WEEK, AND TWO DAYS IN

“Parents, group, it’s a big night,” Mitch booms into the mic. “I need the following Straightlings to come stand at the front with me: Eva Black, Steve Kettle, Deidre Smith, Rob Robinson, Sal Oak, and Cyndy Etler. Parents of newcomers, I want you to take a good look at these clear-eyed, iron-spined young people, because they represent your child’s future.”

We six Straightlings stand military-still in the space between the group and the parents. We’re lined up like slaves on an auction block. Mitch looks each of us in the eye, then looks back at the throng of parents.

“The commitment you made this week, newcomer parents? To trust Straight, to sacrifice, to make any necessary investment of time and money? That commitment will pay off the day your druggie kid is standing here, ready to graduate: honest, loving, and dr

ug free. On that day, we will proudly hand your child back to you, to go out into the world and thrive. To carry Straight’s message to other druggies. And, by the grace of God, to remain Straight. Congratulations, Eva, Steve, Deidre, Rob, Sal, and Cyndy. You are now, officially, graduates of Straight, Inc.”

The mass of parents, the hundreds of Straightlings, they roar and clap and whistle. But we six, suddenly freed—we’re in a standing coma. We have clenched jaws and fists and hearts and bowels. Freedom is a slippery slope.

Still March 1987

Masuk High School, Principal’s Office

THREE DAYS OUT

“We’re so glad you’re returning to Masuk, Cyndy. Do you know how special you are? You are our only clean and sober student. You’re going to be a powerful influence on the student body! If you will excuse me for just a moment, I’ll get your file.”

Click.

“Mom, I’ve got to pee.”

“So go pee.”

“No, you have to take me! I’m not allowed to go to the bathroom by myself!”

“Cyndy, that’s enough of that. You’re out of the program. There are no more rules.”

“B-but—but this is my druggie high school! My druggie friends are out there! I—I can’t—”

“Now you listen to me: we are done with that. Don’t bother me with any more of your rules and permissions!”

“But I’ll die! I’ll be using in a week! I’ll be in a ditch, sucking the devil’s cock! I’ll—”

SLAP.

“Cynthia. Drew. Etler. Stop this. Now. I’ve done my part. I put you through Straight. Now go to the bathroom or wet your pants. It’s your choice.”

Click.

“Okay then, Mom, Cyndy! Thanks for being patient. Here’s your reenrollment paperwork. Mom, if you’ll sign here, we can get Cyndy’s schedule made up. She can start back at Masuk bright and early tomorrow morning. We’re so glad to have you back, Cyndy.”

3

MAY 1987

TWO MONTHS OUT

I can’t believe I don’t get in trouble. I mean, every single day, I walk in late. Just, whenever I get here. And nobody says a word.

At Straight, I would get slaughtered for this. But at Straight, I had oldcomers and host sisters to force me up from the safe, sweet coffin of sleep. Now, it’s just me. I let myself stay dead a lot longer.

When I finally get here, I come in that side door nobody ever uses and follow the silent, empty hallway to math class. If a teacher has her door open, the classroom full of faces turns and drop-jaw stares at me. Fuck ’em, though. I lift my giant Dunkin’ Donuts mug at them, like, Top o’ the morning, suckers.

That’s what makes Blanca Halliwell talk to me—my Dunkin’ Donuts mug. You would want to talk to me about it too. You’ve never seen anything like it. Picture a beehive, with those puffy bump-lines wrapped all around it. Now chop the hive in half and stick a handle on it, plus a faded orange “Dunkin’” and a faded pink “Donuts.” That’s my mug. You can fit a half a coffeepot in there, which I do, every day.

Still. Blanca Halliwell? She’s got the prettiest hair in all of Masuk: long and blond and curly. She’s a cheerleader, she never smiles, and she drives a Jetta. Does she not know about me?

I sit behind her in social studies, which is the boringest class ever. So she kills the boredom one day by spinning backward and grabbing my mug. It’s as if she can’t see the inch-thick cube of Plexiglas, plus barbed wire, plus the flashing, red sign that says STAY BACK! surrounding me.

“You’re always carrying this,” she says, laughing. “What do you have in here? Vodka?” Then she brings it to her nose and smells it.

I’ve been out of Straight a couple months now, so I don’t totally flip. But if she’d asked me if I drank vodka when I was still in the program? Oh my God. They woulda carried me out of that room in a straightjacket. I guess I’ve gotten a teeny bit chill since then, ’cause I just say, “No, it’s coffee. My latest addiction.” And she laughs at me. Or with me, I guess. Which is a huge difference.

Thank God she turns forward then, ’cause what the hell else can I say? I’m an addict. That’s all I got. But when I tell you it’s a miracle that Blanca Halliwell talked to me, believe me: it is a miracle. Nobody talks to me. Except the teachers. Which somehow underlines the fact that nobody else does.

You know what makes it even worse? When I first got back from Straight, the cool kids tried to talk to me. The cool kids who were my druggie friends back when I was drinking and drugging. Or at least, when I would have been drinking and drugging, if I’d been able to get alcohol or drugs. My first day back at Masuk, my best friend Joanna came right up to me! It was like the sun rising after some horrible midnight earthquake: the best and the worst thing that could happen all at once. I stutter-stepped away from her, head tucked in my armpit, then hid in the bathroom for two hours, trying to scrub the shit off my undies.

Joanna is everything, but she’s also the most dangerous thing. For thirteen years, before I met her, I never had an actual friend. Then I had Joanna. For three whole months! Then I got put in Straight and learned she was a bad influence. A druggie friend. And now, I’m back to having zero friends. Actually extra zero because I’m the freak who disappeared one day, then came back a year and a half later as a program zombie. People can’t wait to not be friends with me.

Truth, though? I want Jo back as my friend. More than anything. But if Straight heard me say that, I’d get creamed. I’d get slapped back in there so fast, our heads would spin.

So yeah. When you’ve been locked in a warehouse for sixteen months of tough love therapy, converting back to the real world is hard. School is this daily Roman gladiator match: druggie friends on one side, nosy teachers who want to “help” on the other. I’m in the middle, holding my Dunkin’ mug like a shield, as the Blancas and Brents and Kathys, the eagle-eyed popular kids, watch from the sidelines. As the dungeon of Straight, Inc., looms in the background, waiting for me to screw up. Could you blame me for daydreaming suicide?

Suicide doesn’t run in my “family,” if you can call it that. Crazy does. And mean. But not suicide. The people with my DNA, they keep on living. Living and bitching about it.

Except my father. He ducked out early, but that wasn’t suicide. It was more like popularity. People—my mother, his ex-wives, his students, his kids, his fans—they loved him so much, they crushed him. He crawled into a hospital one day, a year after I was born, and dropped dead. Doctor said maybe it was pneumonia. I know better. He was too bright a star for this world. He just couldn’t last here.

I wonder what he’d think if he could see how his last wife—my mother—and his kids are living now, in the big, rotting house my mother and her second husband, Jacque, found when she got pregnant again. The one with all these bedrooms for her kids + his kids + their kid. The one with enough space for everybody’s secrets.

It feels like, when they sent me to Straight, the hole I left became a vortex. All the secrets got sucked into it, and my mother couldn’t ignore them. I’m just guessing, though. I wasn’t here to see it. But now, eighteen months after she sent me away, the only people left in the house are my mother and my baby half sister. And me, of course. But I disappear so much, I barely count.

Believe me, you wouldn’t pull up a chair in this place, either. Every surface is sticky with old food, mother junk, and sickening memories. I shoosh along the path I’ve made from the front door to the coffeemaker to the cracker cabinet to my room. Occasional field trip to the bathroom, but only when my mother is at work. Your goal would be the same as mine: Don’t. Get. Seen.

My mother is like handcuffs. If she sees you, don’t even try to run. Don’t touch anything. Just put your hands in your pockets, put on your pity face, and nod. When she pauses, go, “Oh, that sucks for you, poor thing.” She’ll stop, eventually. Give it an hour. And know, know, you’ll be staying with

my baby sister for all of next Saturday. Unpaid.

She’s gonna bitch about everything. Her support group, Al-Anon, taught her about how her life is full of alkies: her father, her husband Jacque, me… And how we’ve all been so cruel to her, even though she’s tried and tried to please us. She’ll tear up when she tells you about Her Alvin, my father. How he was the only one who ever loved her, and how she only had him for seven years. She’ll perk back up, though, when she gets to Straight. Straight, Inc.! Straight saved her by introducing her to Al-Anon, by showing her how her alcoholic, druggie daughter was ruining her life!

Go ahead. Ask me how I could possibly be an alcoholic and drug addict when I only drank once and smoked pot twice. I see that raised brow. You just don’t get it. You don’t know what a dry druggie is. But I’ll clue you in. A dry druggie is someone who has the Disease—alcoholism and addiction—even if they haven’t started using yet. Just because the substance isn’t in the person, that doesn’t mean the disease isn’t. You know that saying, “if it quacks like a duck”? Well, how about “if it acts like a druggie”? Yeah. Straight taught me plenty too.

When my mother’s done crying, she’ll go up to her bed and snuggle with her Al-Anon flyers. She’s got a thousand of them, all over her bed and nightstand. She’s also got five Hazelden “recovery meditation” books: Daily Meditations for Women Who Love Too Much, Daily Meditations for Women Who Work Too Much, Daily Meditations for Daughters of Alcoholics, …for Wives of Alcoholics, …for Mothers of Alcoholics. They’re all yellowed and thumbprint-y. They’re her new blankie.

And I totally get it. Straight is my frigging blankie. Okay, it was hell until I accepted my addiction. But now? Like, if I could go back and be on staff? I’d do it in a millisecond. I’d staple myself to the back wall in a sleeping bag and only come out to lead discussion groups. Oh my God, can you imagine how safe life would be? Living where everyone gets you? It would be the opposite of this plague, slunking through Masuk and chipping away the hours in this house.

The only reason I can sort of deal is because Jacque is gone. In my mother’s great flash of awareness, she realized that Jacque’s not good for her, so she’s divorcing him. Thank you, Jesus God. When I was in Straight, I had to tell him—gah. We all had to say “I love you” to our parents, which meant I had to say it to my mother’s husband. And I had to apologize for making him do things to me. Because everything was my fault, so I had been, like, acting flirty when I was a four-year-old, I guess. Which made him…

We Can't Be Friends

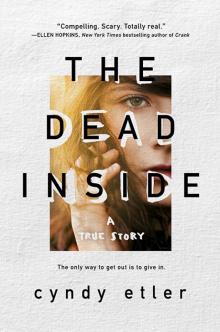

We Can't Be Friends The Dead Inside

The Dead Inside