- Home

- Cyndy Etler

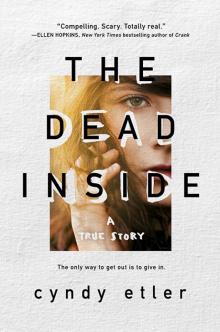

The Dead Inside Page 5

The Dead Inside Read online

Page 5

I haven’t been in Spanish five minutes when a knock pulls all eyes to the door. The knocker opens the door without waiting for a come in. A woman scans the class while faking an apology. That’s when I put my head down.

“I’m sorry to interrupt, Mrs. Rosenstein, but I have a bit of an emergency with a parent.” The bad vibe officially kicks in. “Do you have a Cynthia Etler in this class?”

I knew it. I shoulda hid in the Azores’ attic in Bridgeport.

As if she’s in shock from being interrupted, Señora Rosenstein says nothing for a sec. Then she goes, “Yes, yes I do. Cynthia…Etler, where did I put you? I just rearranged my seating chart…”

My forehead is on my desk, so I can’t see these two bitties, but I can feel them scanning the seats with their laser-beams. Still, I don’t budge. No way am I volunteering for this shit.

“Cynthia Etler? Cynthia, where are you?”

Somebody kicks the leg of my chair, undoubtedly the asshole jock behind me. I don’t think school employees kick students, usually. Still, I better say something. It’s not like they’re not gonna find me.

“Yeah,” I heave out as I stand. “I’m with ya.”

Everyone stares at me as I move toward the door. Someday, I swear, I’m gonna live where nobody can see me.

It turns out the lady at the door is my guidance counselor. She’s got her hair in the Connecticut bob, like she wants to be all Fairfield County. But her clothes are totally Dress Barn. If she’s nice to me, I’ll feel sorry for her.

“So, you’re Cynthia?” She’s smiling as her heels click down the hallway, but I don’t answer. “I’m Ms. Grass. If you struggle in your classes, or your peer relationships become challenging, I’m here for you.”

I study the tiny diamond in her earlobe. It’s smaller than your average pencil point. Yeah, I feel bad for her. She’s trying pretty hard.

She chatters the whole way to her office, but when we step inside, she gets serious. She gestures toward a chair, then turns on a little machine. A swishing noise kicks in, I guess to cover our “talk” from eavesdroppers. As if I’m going to be sharing heavy secrets with this lady. I feel extra bad for her now.

“So, Cynthia,” she says. “What’s going on with you?”

She must not remember the hot pink WHILE YOU WERE OUT slip that’s front and center on her desk. She already knows what’s going on with me, or at least what my mother says is going on.

Nadine Etler, parent of Cynthia Etler—VERY CONCERNED—Student gone since Thursday. Mother TERRIFIED. Use caution! Student may be volatile!

Awesome. Volatile. We learned that word in eighth grade vocab: it means crazy violent. To my mother, I’m the volatile one. But I gotta hand it to Ms. Grass. She’s doing good for someone alone in a room with a crazy, violent teenager.

There’s nothing to say, so I say nothing. But it’s okay. Ms. Grass is the type who doesn’t mind doing the talking.

“Your mother called the school, Cynthia. She’s looking for you. She’s very concerned that you weren’t home over the weekend. I haven’t spoken with her personally, but I assume it’s a simple mix-up—confusion about which friend you were spending the weekend with?”

“Oh, yeah. Totally. She’s just confused. My neighbor should’ve reminded her I was staying at their house. I’ll call her from the pay phone.” I even sort of smile.

“Well good then, Cynthia!” She brings her hands together in a clap. “You may use my phone, if you’d like.”

“Nah, that’s okay. I don’t want to take up your office. I’ve got a dime. I’ll call her at lunch. Thanks, though.”

“Well, Cynthia, you’re most welcome. Really, I have no idea why anyone would say—well, you’re a thoughtful young lady. Let me write you a pass back to class.”

I have the smoking pit to myself for the rest of the period. My mother figured out I wasn’t at Dawn’s this weekend, and now she’s after me. Jo only asked if I could stay with them for the weekend, and the weekend’s over. I sit and smoke and try not to let myself think.

• • •

I don’t see Joanna at lunch, which is weird. Somebody said she had to stay in science for a make-up test, but Jo? No way. Badasses don’t do makeups. My insides feel like a dried-out sponge. Scratchy, holey, and easily snapped in half.

I don’t see her at the end of the day, either. Her bus is the first one to leave, and I don’t get out front ’til after it’s gone. Mrs. Skinner—the one cool teacher, who notices stuff—kept me after class, like, “Are you okay, Cyndy?” At least she knew enough to be writing in her grade book instead of that deep, caring eye contact bullshit. But there’s nothing she can do for me. You can’t go live with your teacher, so there’s no point telling her anything. And her caring only made shit worse, ’cause it made me late for the bus, and now I can’t find Jo. So I have no idea where I’m supposed to go tonight.

I’m running along the row of buses, hoping for a miracle, like Joanna’s face in the window of a bus that hasn’t left yet. Instead, six steps ahead of me, I see tight-ankle work boots and lightning-wash jeans. Skinny ass, limp perm. It’s her.

You know how sometimes when boys are standing around, picking teams or whatever, and a strong kid will pound the basketball hard, with both hands, down at the pavement? Know how the ball rips back upward, like it wants to kill him? That’s what my blood does when I see her: it rips through me like I can do anything, including beat the shit out of Kara Anderson.

“Kara Anderson!” It’s the same tone the cheerleaders used when they told the whole cafeteria I had a free lunch card in seventh grade. But I’m even louder. Her perm twirls out around her head as she turns.

“You been talking about Joanna Azore?” My voice sounds like someone else’s. But she might not even hear it, ’cause I’m handcuffing her shoulders and shaking her like a baby rattle. And oh my God, does it feel good.

In the back of my brain I hear the slats of bus windows opening, the roar of kids cheering. But that doesn’t matter. Nothing does, except this power. This rush. This hate. I throw Kara onto the sidewalk like she’s the basketball.

“You don’t! Fucking! Talk! About! Joanna!”

I’m pulling my fist back to hit her when I see the security guard huffing toward me and some suit-wearing grown-ups right behind him. Time for me to fly.

7

PERMISSIONS MUST BE REQUESTED 72 HOURS IN ADVANCE & BE OKAYED FIRST BY PARENTS, THEN STAFF

It’s a long walk to Jo’s from school, especially when the walk starts with running from a pack of pissed off adults. Every time I hear a car behind me, my stomach curls like a fist. Is it a cop? Are they after me? I turn to look at cars as they pass, but instead of a blue-hatted cop named Rudy, fleshy little kids stare at me through the windows. What, they’ve never seen someone hauling ass before? I hate this town. God, gimme Bridgeport.

I had sprinted down the Masuk driveway—I mean, there was smoke coming out of my footprints. But now, a half-hour up the road, I’m walking regular. My feet match the drums in Zeppelin. “Houses of the Holy.” Thank God for my headphones.

I guess normal kids have different people to give them what they need. A mom for hugs and a dad for fun and safety. They have grandparents for buying them stuff, and cool aunts and uncles to teach them what their parents won’t. I don’t have that kind of family. My mother is not a Band-Aid giver. And the other relatives I have—Uncle Bob and Aunt Judy, the Etlers from my father’s life before me—my mother doesn’t like them, or they don’t like her or something. I pretty much never see them, so I don’t have them.

But I’m okay. The way other kids get their needs met from their family, I get what I need from my music. When I put on my headphones, I’m in a world that cares. Like this song, “No Quarter.” It’s about kids with no homes, with no “quarters” to stay in.

The voice ripples in a way that breaks your

heart, and a piano plays sad notes that say, “We get you.” It’s like you’re listening to heaven, and heaven’s telling you that everything is gonna work out.

Zeppelin understands kids like me, how no doors open for us. But they also say there’s a reason for what’s happening. I may not get it yet, but that’s okay. ’Cause I have Zeppelin. And Floyd. And the Stones. My headphones are my quarters. So I’m okay.

• • •

When I get to Jo’s I ring her doorbell. It plays a whole friggin’ song when you press it. But when the song ends, I’m still standing there. So I press it again. That’s when Mrs. Azore opens the door. Doorbell music is playing as we both start talking at once.

Ding

Ding

Ding

Dong

“Hey, Mrs. Azore. Is—” / “Cyndy, I just spoke with—”

Ding

Ding

Ding

Dong

“—Joanna here?” / “—your mother. I’m sorry. You can’t stay with us anymore.”

CLANK.

That’s how the song ends, with the brass knocker clanking out the period as the door closes hard.

• • •

By the time I get to Dawn’s, the sun’s going down. Through their back kitchen window, I see the family around the dinner table. They’re having macaroni and cheese and hot dogs and milk. My stomach growls, and not just for the food. I sit down on the top step and look at the sunset. I’ll knock after they put their dishes in the sink.

Dawn ends up saying I can sleep on the daybed, in their upstairs front hallway. It’s parked right under the window that faces the road. If I put my face in that window, I’m looking at my mother’s house. I’m not letting my face get anywhere near that window. Windows work in reverse too.

By the time I go to finger-brush my teeth, her kids are asleep. The house is all quiet. But right when I sit down to pee, I hear Dawn and John go into their room and close the door. I wasn’t planning on spying on them, really. But as I creak the bathroom door open, I hear my name in a slanty tone. Like, Cyndy.

It’s John. Straight-up-and-down John. Toyota-driving, never-take-a-day-off-work-John. John who’d love to help me, if he could do it without breaking any rules. Maybe John’s never seen real evil. Maybe that’s why he doesn’t get the deal with Jacque.

“We have to tell them she’s here,” says John.

“John—” goes Dawn. She understands shit.

“They consider it kidnapping, Dawn. The police are involved. Are you going to call Nadine or should I?”

It’s quiet for a minute. I picture all of Dawn’s dolls listening to their conversation. I hope, like John, they don’t understand bad stuff. A floorboard creaks, then Dawn’s voice.

“I’ll call her.”

Quiet as smoke, I’m back in the front hall, under the scary window. My stomach is a bad science experiment as I try to get my Levi’s on without standing up in front of that window. They’re scrunched around my ankles when Dawn walks in.

“Packin’ up?” she asks, pulling my Jansport toward her.

“Well, yeah. I heard you guys. Sorry. I’m outta here.”

Dawn pulls the zipper on my pack back and forth as I lie down and bridge my butt up, then pull my jeans on the rest of the way. When I suck my belly in and start buttoning, Dawn speaks.

“I’m not gonna do it,” she says.

I sink the bridge down to see her better.

“Huh?”

“I’m not telling your mother you’re here.”

She stops zippering. She told her husband she’d do it, but she’s not going to. Which means she lied for me.

“Really, Dawn? You won’t call her? ’Cause if they find me, I’ll be—”

“I’m not calling her.”

“You promise?”

I pick my eyes up enough to look at hers, and dag. I’ve never seen Dawn with mad in her eyes. I hope I never see it again.

“I’m not calling her. But I’m telling John I did.”

I should thank her, but that would feel so flimsy. Dawn pushes herself up and gives me this weird hug, where she’s standing and I’m on the floor.

“G’nite,” she says, with her normal Dawn face back on, before going down the hall to her room.

When they’re all asleep, I go out and sit on the back porch. The night smells just like Bridgeport. I guess October smells the same wherever you go.

I can’t stay here after tonight. By tomorrow, my mother and Jacque will know where I am. John will call them. So tomorrow night, I’ll be wherever. I don’t know where wherever is, but I know, at least, what it will smell like.

8

NO HITCHHIKING OR PICKING UP HITCHHIKERS

Tina’s drawn to me like Jesus to the pathetic. Something about her fat-girl, frosted-hair, ranch-house life needs to save someone, and here I am. She was nowhere to be found last year, when I ate my lunch in a bathroom stall. But now that I’m a smoking pit hero? Poof! Here she is with an offer to stay at her house. I guess she heard about Jo’s parents’ shutting me out. I guess everybody has.

When I called Steve from Dawn’s Monday night, his dad said I can’t stay there either. So my new home was about to be a sleeping bag under a highway bridge. Me, the needles, and the used rubbers. Then Tina comes bouncing up.

“Hey, Cyndy! What’s up!”

Like we’re great friends or something. I raise an eyebrow at her, ’cause she’s only trying to impress the juniors I’m sitting with.

“Hey, anyway, Cyndy,” she goes, “I heard you—I mean, I heard Joanna’s—hey, if you need a place to stay, my father said it’s okay. You can come stay with us.”

Us. What a word. Two letters that hold everything I’ve ever wanted. Some people can throw their “us” around, all casual like that. If I had an “us,” I’d carry it in a little satin bag, with both hands cupped around it. But for Tina, it’s just a lure. Still, she’s offering her “us” to me. That’s better than a bedroll and a bridge.

So now, pretty much, I have a new best friend. I’ve just gotta tell Joanna it’s only for show. Jo will always be my real best friend, even though I haven’t seen her since she took off down the hallway Monday morning. Where is she?

But Joanna or not, I’m a rock star in the pit now. No joke. I get off the bus at school Tuesday morning—after the creepiness of walking to the bus stop from Dawn’s, praying nobody sees me—and I walk into the pit…and it goes silent. I go down the steps and people—I’m talking hoods here, including seniors—step back and clear a path for me.

“Hey, Cyndy. How you doin’?” someone says.

I keep my eyes straight ahead, ’cause for all I know, they’re making fun of me. Except they totally aren’t.

One of the big, silent dudes peels himself off the wall, comes over, and puts his hand on my arm.

“How you doin’, Etler? Come hang with us.”

Next thing I know, I’m sitting in the coolest, scariest spot in the pit, just me and these guys. And I got invited. By name.

Other than being big, these guys are cool because they don’t talk. They’re like gargoyles, so still you’re not even sure they’re alive. But one of them moved for me. And another one spoke.

“Hey, heard about your sitch, Etler. That’s rough.”

So the cool people know my name and they’re talking about me when I’m not there? Holy crap. I guess homelessness + kicking poser ass = badass.

So I’m sitting there with the gargoyles Tuesday morning when Tina comes up. She looks all teenybopper, even to me. Like the clown on the spring in the jack-in-the-box.

“Hey, Cyndy! What’s up!” Boing! Doi! Boing!

And it hits me, oh my God, I’m looking down on somebody. Fuckin’ A. I’m, like, cool. On the inside. But I should be nice because, thanks to Tina, I get to

sleep in a bed tonight. It’s tucked in a corner of her basement. What is it with me, beds, and basements? At least at Tina’s, somebody hung a sheet so I have privacy.

So staying at Tina’s is okay. Her mom is one of those ladies who wears rollers and watches soaps all day, and her dad is—you ready? A hairdresser. No, really. Not a barber, a hairdresser. He does Monroe ladies’ hair in a beauty shop.

And Tina’s all right, too. Seriously. She talks like the Tasmanian Devil, fast and nonstop, but at least I don’t have to figure out what to talk about. And anyway, the only time I have to see her is in the morning and afternoon, when we take the bus. Somehow she picked up on the message to not come in the smoking pit anymore. Chunky, pink-sweatshirt, no-cigarette Tina, talking to me on fast forward? No sir.

On Thursday, after my second night at Tina’s, Jo comes up to me. I’m like, huh? I mean, she’s totally been avoiding me. I don’t know if she’s pissed I’m staying at Tina’s or what, but here she is, heading for my new spot with the gargoyle guys. She pushes her fist toward my hip and goes, “Early birthday present.” I slant my eyes from her fist to her face, and she knocks her chin at me.

“Go ahead,” she says.

I lay my hand flat, and she uncurls her fist. A blue velvet bag, the weight of a lemon, drops into my open palm.

“Jo. Your pipe?”

“Happy fourteenth, Cynd. Make it a good one.”

I want to ask her how. How do I make it a good one? But she’d just say, “Smoke up, man!” I’d so be a loser if I asked her how to do that. But seriously, I still don’t know. I’ll take, like, one paranoid hit, terrified I did it wrong while everyone watches. Then I act like I’m too stoned for more, and sit there praying bullets some Zarzoza doesn’t say what everybody’s thinking: “You’re such a poser. Get the fuck outta here.”

Anyway, speaking of my birthday, I bet you ten bucks that’s why I haven’t been called back to the guidance office. My mother stopped looking for me because she doesn’t want me back. Not yet. If I’m not there on my birthday next week, she won’t even have to bake a cake. But October 18? Day after my birthday? I’ll be right back in Ms. Grass’s office. Watch. My mother will call the school the second it quits being about me, and can switch back to being all about her.

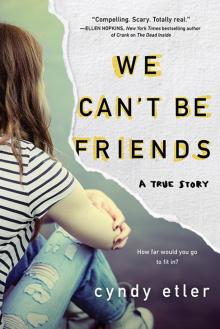

We Can't Be Friends

We Can't Be Friends The Dead Inside

The Dead Inside